Lectio Divina

The practice of prayerful reading

Click here for the daily Mass readings

The Rule of St. Benedict allots a significant place in the daily monastic horarium to the practice of Lectio Divina, or “divine reading.” This style of prayer was in fact common practice among Christians of the first centuries and has returned to popularity in our day.

It is a very simple approach, readily available to anyone interested in praying with the Bible. Descriptions written to describe common experience make this style generally identify four “steps” or aspects of the prayer, but these are descriptions, not rules. One should follow the promptings of the Spirit in deciding how long to devote to each aspect. In fact, quite often it isn’t possible to tell which aspect one is engaged in, as they flow fairly freely, one into the other, as you pray. And you can move back and forth among them as you feel drawn to do so.

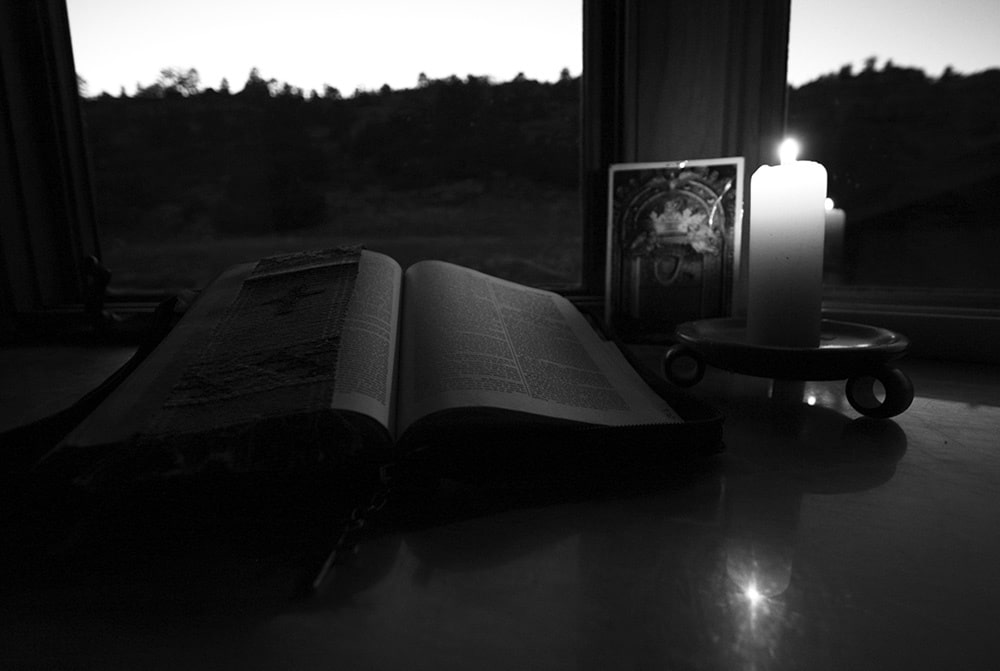

In general, before beginning to pray, it can be helpful to decide on a time, place and environment conducive to quiet concentration and to follow a regular routine, especially when prayer grows dry and uninteresting.

Lectio divina is really a way of surrendering the imagination to God. We all know that our minds are busy all day long, sometimes with worthwhile thoughts, sometimes with destructive ones. The habit of regular lectio divina provides food for thought to which we can return throughout the day, repeating familiar passages or reconsidering reflections, whenever the mind falls idle or starts down the path toward unkind thoughts, criticisms, worries, and all the other unhealthy habits of thought that stand between us and the gift of dwelling in God’s presence in peace.

1. The first step is “lectio”: Reading

You can take any section of the bible, or even some other piece of religious reading. Some people prefer to use the readings provided in the daily lectionary for Mass. Others prefer to follow a particular book of the bible from beginning to end. Others prefer to move among related passages. Whatever you’re reading, lectio requires that you read it very slowly to allow it to sink below the surface of your mind. You can mouth the words, or even read them aloud, to help you to slow down and focus. You can read a whole passage to get an overview and then go back and repeat parts of it, or you can read very slowly from the beginning. What matters is that you read attentively, prepared to pause for meditatio and oratio when something strikes you.

2. The second step is “meditatio”: Meditation

Meditatio can take one of two traditional forms. Perhaps the oldest is the simple repetition of the text without a lot of analysis, allowing the words to sink deeper and deeper into the heart as you memorize them. It’s amazing how much work they can do to rebuild our inner ways of looking at the world without a whole lot of conscious effort (and control) on our part. The other form involves thinking about the text actively — questioning it in light of your experience and allowing your experience to be questioned by the text. Either or both form can be useful.

3. The third step is “oratio”: Prayer

This is the point at which reading and thinking turn into explicit conversation with God, either in words or simply in wordless directing of thoughts and feelings to God.

4. The final step is “contemplatio”: Contemplation

This is the point at which words give way to silent presence, either briefly or for longer periods of time, depending on the individual and the gift of God. It is the part of prayer in which God is more active than we are. It can’t be commanded, only accepted. When it ends, it’s time to go back to reading again.

Suggested reading:

Casey, Michael, OCSO. Sacred Reading: The Ancient Art of Lectio Divina. Liguori MO: Triumph Books, 1996

Verbum Domini by Pope Benedict XVI